Beijing’s balancing act: Cooperation and competition between China and Central Asia

China’s overtures to the five post-Soviet republics of Central Asia have produced a mixture of partnership and rivalry that is reshaping Eurasia’s...

China’s overtures to the five post-Soviet republics of Central Asia have produced a mixture of partnership and rivalry that is reshaping Eurasia’s political map.

Trade is booming, flagship rail and energy corridors are inching forward, and regional capitals increasingly look to Beijing for technology and finance. Yet concerns about debt burdens, security influence and public backlash reveal a competitive undercurrent.

1. A Commercial Boom, but on Beijing’s Terms

1.1 Trade and Transit

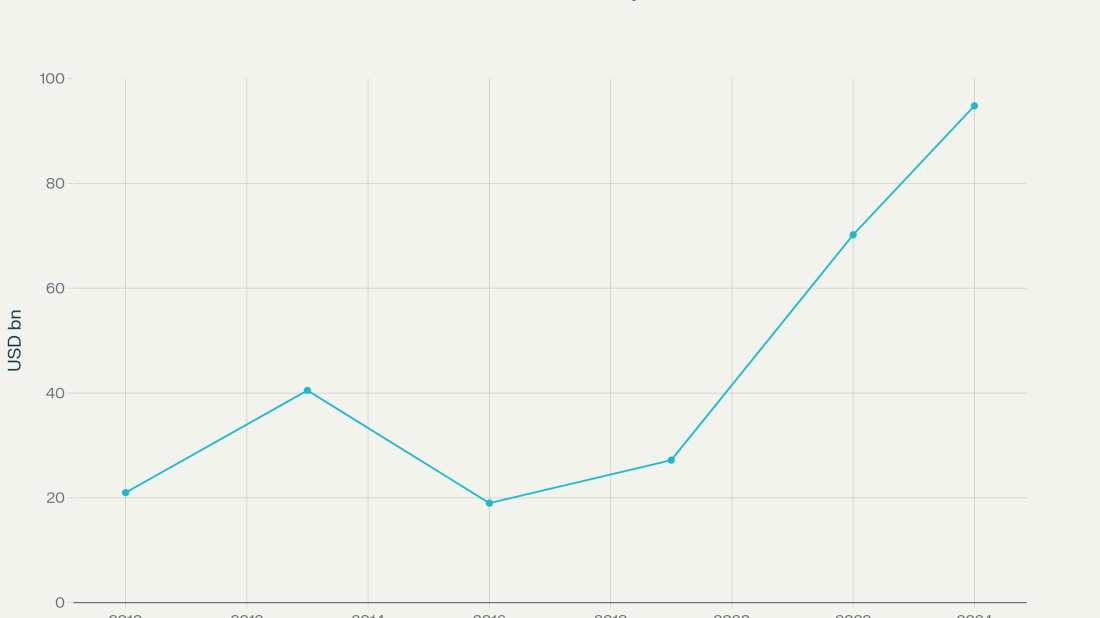

Chinese-Central Asian trade has more than quadrupled since 2010, topping a record $94.8 billion in 2024. A decade of Belt and Road rail links—Khorgos dry port on the Kazakh frontier, the Trans-Caspian “Middle Corridor”, the newly launched China-Kyrgyzstan-Uzbekistan railway—has cut shipping times to Europe and diversified routes that once depended on Russia.

China now buys Turkmenistan’s gas via three pipelines delivering 40 billion m³ a year, with a fourth line under construction to lift volumes to 65 billion m³. In return, Central Asian markets import Chinese machinery, vehicles and digital equipment, deepening supply-chain lock-in.

1.2 Financing and Debt

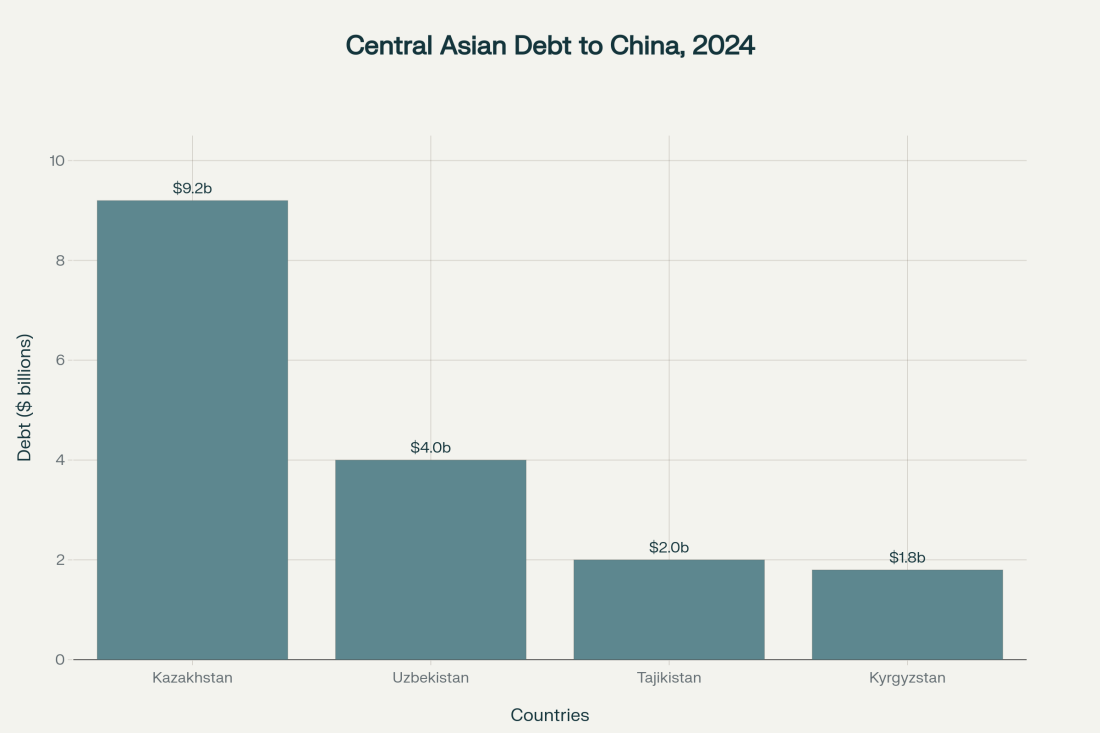

Chinese policy banks have lent roughly $20 billion to the region, funding power plants, highways and telecoms grids. Kazakhstan holds the lion’s share—about $9.2 billion—while poorer Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan owe smaller sums that still exceed 30 per cent of their external debt. Bishkek and Dushanbe have sought rescheduling; analysts warn of asset-for-debt swaps echoing Sri Lanka’s Hambantota precedent.

2. Strategic Convergence: Security and Technology

2.1 Shanghai Cooperation Organisation

Through the SCO, China conducts joint counter-terrorism drills and promotes a common cyber-security code with Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan. Beijing’s framing of “three evils” (terrorism, separatism, extremism) dovetails with local leaders’ concerns over militant spill-over from Afghanistan, giving China a legitimate security foothold.

2.2 Digital Silk Road

Huawei and ZTE dominate 4G/5G roll-outs and data-centre projects in Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan. A $50 million Trans-Caspian fibre-optic cable and Kazakh “Smart City” pilots show Beijing exporting its tech standards. Western critics worry about surveillance exports; Central Asian officials see cheaper connectivity and skills transfer.

3. Fault-Lines and Pushback

3.1 Public Protests

More than 150 anti-China demonstrations since 2018 reveal fears of land leases, environmental damage and Xinjiang’s detention camps. Violence at Chinese-run Kyrgyz mines and factory protests in Kazakhstan forced some projects to pause, highlighting reputational risks for Beijing’s investors.

3.2 Competing Players

Russia, the US and the EU are vying to dilute China’s clout.

3.3 Debt and Governance Risks

Ratings agencies flag Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan as vulnerable to debt distress if commodity prices slide. Civil-society groups question opaque tendering and Chinese labour imports that limit local job creation. Beijing has granted some payment deferrals but rejects outright write-offs, reinforcing perceptions of hard-nosed “creditor diplomacy”.

4. Outlook

Conclusion

China’s push across the steppe is neither a neo-imperial land-grab nor a benign development crusade. It is a calibrated strategy blending infrastructure finance, market access and selective security support that Central Asian governments have welcomed to diversify partners and bankroll growth. Yet the asymmetry of power, rising debt and social backlash create a competitive dynamic increasingly shaped by third-party entrants. How Astana, Tashkent and their neighbours manage this delicate balance will determine whether Beijing’s Eurasian pivot becomes a platform for shared prosperity—or a new arena of great-power rivalry.

A series of earthquakes have struck Guatemala on Tuesday afternoon, leading authorities to advise residents to evacuate from buildings as a precaution against possible aftershocks.

A deadly mass shooting early on Monday (7 July) in Philadelphia's Grays Ferry neighbourhood left three men dead and nine others wounded, including teenagers, as more than 100 shots were fired.

Australian researchers have created a groundbreaking “biological AI” platform that could revolutionise drug discovery by rapidly evolving molecules within mammalian cells.

Dozens of international and domestic flights were cancelled or delayed after Mount Lewotobi Laki Laki erupted on Monday, but Bali’s main airport remains operational.

French member of parliament Olivier Marleix was found dead at his home on Monday, with suicide being considered a possible cause.

Georgia's Ministry of Foreign Affairs has abolished units working on inter-agency coordination of the European and Euro-Atlantic integration process, which is considered as a part of a broader effort to halt the country’s integration into the European Union.

Clashes between Druze and Bedouin Arab tribes continue in Syria’s southern Sweida province, near the Jordanian border, while six soldiers were killed in an attack by Druze forces on Syrian army units deployed to restore order in the area.

The High-Level Political and Security Dialogue between the European Union and the countries of Central Asia held in Dushanbe, Tajikistan.

Baku and Kyiv have signed an economic cooperation plan during the 13th meeting of the Intergovernmental Commission on economic cooperation between Azerbaijan and Ukraine as well as discussed gas supplies.

The Foreign Ministers of European countries have released a joint statement on recent developments in Georgia, expressing deep concern over the deteriorating situation in the South Caucasian country. The ruling Georgian Dream party issued a sharp condemnation of the joint statement.

You can download the AnewZ application from Play Store and the App Store.

What is your opinion on this topic?

Leave the first comment