Iran designates EU naval and air forces as ‘terrorist entities’ in reciprocal move

Iran announced on Saturday (21 February) that it has designated the naval and air forces of European Union member states as “terrorist entities” i...

In the pre-dawn darkness of Funafuti atoll, 16-year-old Teleke Palani races across a coral causeway as spring tide waters creep across the pavement, her phone capturing the encroaching sea that threatens to swallow her homeland whole.

Each step documents another piece of disappearing Tuvalu - part of an emerging global coalition of nations and communities living precariously at or below one meter above sea level, fighting not just for survival, but for a radical reimagining of climate justice itself.

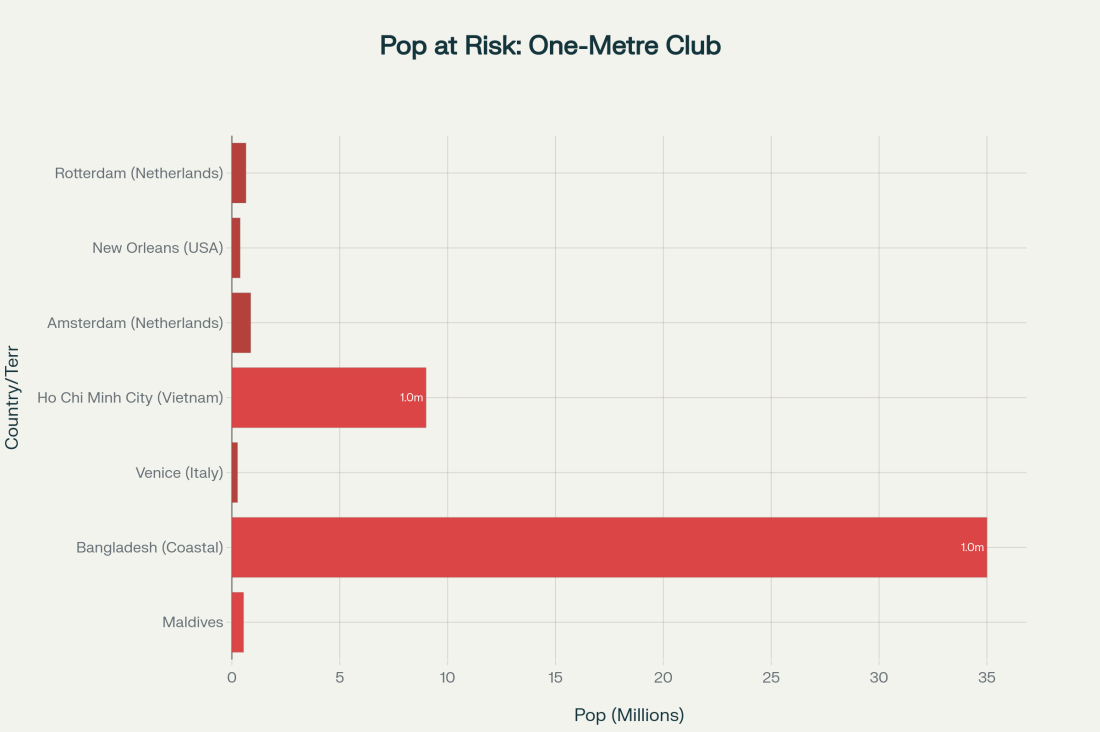

This is the story of the "One-Metre Club"- a term describing the approximately 190 million people worldwide living in regions at or below one meter above current high tide lines. From Pacific coral atolls to Bangladesh's subsiding deltas, from engineered Dutch polders to Louisiana's hurricane-battered bayous, these frontline communities are reshaping global climate debates and forcing an unprecedented reckoning with loss, damage, and sovereignty in an era of rising seas.

The Mathematics of Disappearance

Global sea levels have risen 216 millimeters (8.5 inches) since 1880, accelerating to 3.4 millimeters per year - more than double the 20th century average, with vulnerable Pacific regions experiencing rates up to 10 millimeters annually. Under current trajectories, scientists project 430 to 840 millimeters of rise by 2100, with acceleration rates potentially reaching 15 millimeters per year under high emission scenarios. Climate Central's 2024 analysis using improved elevation data shows that under high emissions with Antarctic instability, up to 630 million people live on land below projected annual flood levels by century's end.

Three Oceans, One Crisis

Tuvalu: Digital Sovereignty in the Metaverse

In November 2021, Tuvalu Foreign Minister Simon Kofe made international headlines by delivering his COP26 speech standing knee-deep in seawater. "In Tuvalu, we are living the realities of climate change and sea level rise," he declared, his trouser legs rolled up as waves lapped around the lectern. "We cannot wait for speeches when the sea is rising around us all the time."

That dramatic moment catalyzed Tuvalu's pioneering response: becoming the world's first nation to create comprehensive digital sovereignty. In 2022, Tuvalu announced its intention to build a complete digital replica of itself - preserving governance, citizenship, and cultural heritage even as its physical territory disappears. The initiative includes blockchain-secured digital passports and constitutional amendments declaring that "the State of Tuvalu shall remain in perpetuity in the future, notwithstanding the impacts of climate change".

Finance Minister Seve Paeniu acknowledges the burden: adaptation costs consume 7.6% of Tuvalu's GDP annually in FY 2024/25 - among the highest rates globally. "Although Tuvalu had no large-scale outbreaks, we remain more vulnerable because of the increasing threats of climate change," Paeniu noted.

Twenty-six countries have recognized Tuvalu's digital sovereignty, with Australia formalizing agreements allowing 280 Tuvaluans to migrate annually while maintaining statehood recognition. This radical reimagining challenges fundamental assumptions about territory and sovereignty in international law.

Bhola Island: The World's Fastest Eroding Delta

Half a world away, Bhola Island in Bangladesh represents ground zero for climate displacement. Once covering 6,400 square kilometers in 1965, the island has lost half its territory to erosion in four decades, leaving 500,000 people homeless. The Meghna River carries one million cubic feet of water around the island every second, creating "the highest amount of river erosion in Bangladesh"

Local fisherman Abdul Halim Sheikh from neighboring Koyra exemplifies the human cost. Once well-off with secure income from fishing and plantation work, successive cyclones, tidal surges, and salinity intrusion destroyed his economic base. In interviews conducted by researchers from Brot für die Welt, displaced women repeatedly described losing everything: "The river took our house, our land, our trees - everything we built over generations," said 45-year-old Rashida Begum, now living in a Dhaka slum after fleeing Bhola's erosion.

Government estimates suggest six million Bangladeshis are displaced annually by river erosion, with Bhola representing the most acute example. Yet residents have developed remarkable adaptation strategies: floating schools that follow displaced children, salt-tolerant rice varieties, and mobile boat-building skills enabling rapid relocation as shorelines shift.

Isle de Jean Charles: America's First Climate Resettlement

In Louisiana's coastal marshes, the Isle de Jean Charles Band of Biloxi-Chitimacha-Choctaw Indians became America's first federally funded climate relocation. The island has lost 98% of its land since 1955 due to saltwater intrusion and subsidence.

Chris Brunet, a 57-year-old tribal member, lived his entire life on the island before relocating in 2023. "I can't smell the water, I can't see it, I can't sense it. And I miss it," he reflects from his new home 40 miles inland. But Brunet reframes the narrative: "We are not climate refugees. We are climate pioneers".

The $48.3 million federal resettlement was intended as a model for future climate relocations, but implementation revealed complex justice challenges. Tribal leaders criticized being marginalized in decision-making about their community's future. Chief Démé Naquin noted: "We had all the plans set up and once money was granted, the state took over and the tribe had no more say so".

The Loss and Damage Revolution

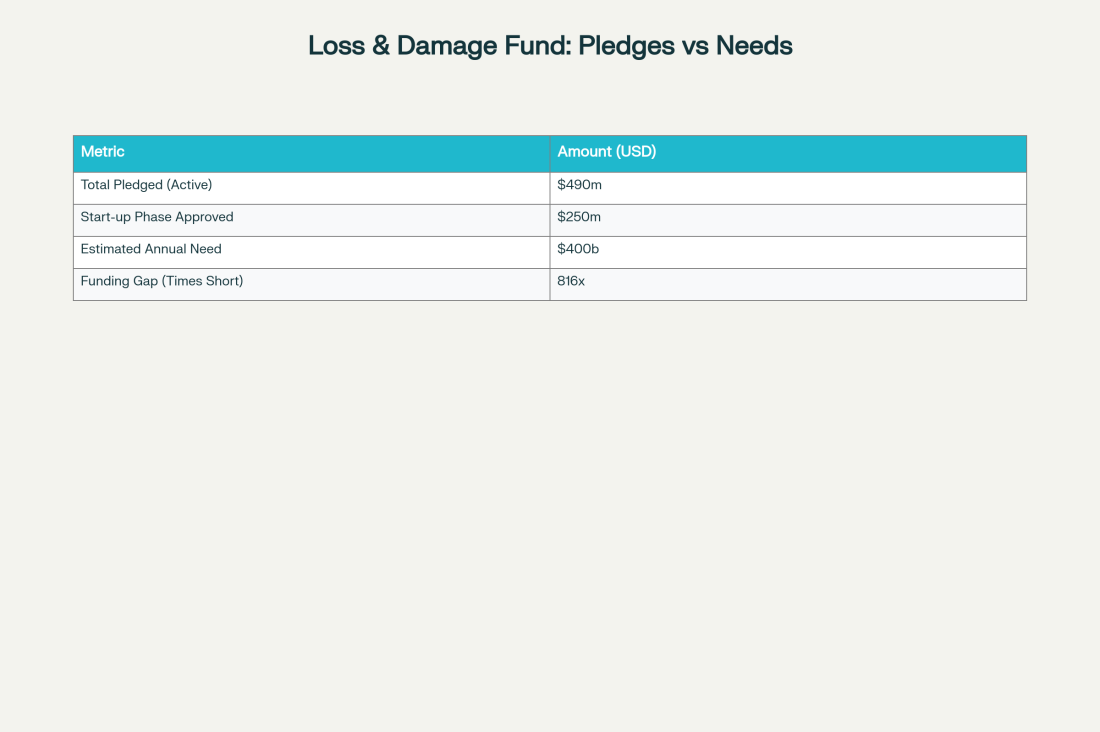

These frontline experiences catalyzed the historic establishment of the Loss and Damage Fund at COP27 in Egypt - a financial mechanism to assist developing countries with unavoidable climate impacts. By July 2025, the fund received $789 million in total pledges, with $348 million actually received, though the United States withdrew its $17.5 million commitment under the Trump administration.

The fund approved a $250 million start-up phase through 2026, prioritizing grants of $5-20 million for national-scale interventions. At least 50% of initial funding is reserved for Small Island Developing States and Least Developed Countries - the most climate-vulnerable regions.

However, the funding gap remains staggering. The Loss and Damage Collaboration estimates annual needs of $400 billion, making current pledges insufficient to meet even 1% of requirements. Barbados Prime Minister Mia Mottley warned that "those who contributed to the problem, must help solve the problem," calling for taxes on flights, shipping, and fossil fuel extraction.

Innovation at the Edge of Survival

Facing existential threats, One-Metre Club communities have become laboratories for breakthrough adaptation solutions.

Nature-Based Hybrid Solutions

Mexico and Fiji have pioneered mangrove-reef hybrid barriers combining coral structures with strategic mangrove plantings. These systems provide superior storm protection while supporting biodiversity and carbon sequestration. Early results show resistance to sea level rise rates exceeding 10 millimeters per year when properly maintained.

AI-Powered Digital Infrastructure

Advanced artificial intelligence systems now integrate meteorological, ecological, and socioeconomic data to provide consequence predictions at 20-meter resolution. Unlike traditional weather forecasts, these AI systems predict impacts - showing which crops will fail, communities will flood, and evacuation routes remain passable.

Microsoft's partnership with Kacific satellites will connect 10 million Pacific islanders through 750 rural institutions over two years, providing the digital backbone for these early warning systems while enabling climate monitoring and cultural preservation as communities face displacement.

The Economics and Politics of Disappearance

Small Island Developing States face adaptation costs consuming 4-7% of GDP - orders of magnitude higher than wealthier, less vulnerable nations. Tuvalu alone spends 7.6% of GDP on adaptation, while the Marshall Islands faces similar burdens.

The sovereignty implications extend beyond individual nations. As sea levels rise, exclusive economic zones may shift or disappear, affecting fishing rights and maritime boundaries. Tuvalu's digital nation initiative specifically addresses this by seeking to fix its EEZ permanently, regardless of physical territory changes. The Warsaw International Mechanism for Loss and Damage has evolved from a technical body to a central pillar of climate negotiations, largely due to frontline community advocacy.

Managed Retreat and Justice

Even innovative adaptation has limits. The IPCC projects technical limits to coastal protection under high emission scenarios, while economic barriers make protection unaffordable well before technical limits are reached. For many One-Metre Club communities, managed retreat becomes inevitable.

The Isle de Jean Charles experience offers both lessons and warnings. While providing safer housing, the process fractured a community living together for 170 years, raising questions about what is preserved and lost in climate adaptation. Brunet's reflections capture this complexity: "The Island is still there, it's real... It's there until the elements say so".

Toward Climate Justice

As Teleke Palani continues documenting Tuvalu's transformation, her footage captures more than rising waters - it records the emergence of new climate activism reshaping global responses. The One-Metre Club demonstrates that climate impacts are not just environmental but fundamentally political and cultural challenges.

These communities have shown that frontline experience drives systemic change. The Loss and Damage Fund establishment, driven largely by small island states, represents a fundamental shift toward recognizing historical responsibility and supporting unavoidable impacts. Their innovations - from digital sovereignty to floating schools to hybrid coastal barriers - pioneer solutions that will become increasingly relevant as climate impacts intensify globally.

The One-Metre Club didn't choose to be on climate change's frontlines, but their responses shape humanity's future. In their struggles for survival, sovereignty, and justice lies a roadmap for a world where every grain of sand - and every human life - counts in the fight for a livable climate.

As spring tide retreats from Funafuti's causeway, Teleke saves her documentation to Tuvalu's growing digital archive - preserving her nation's story regardless of what happens to its physical territory. In her work lies both warning and hope: warning of catastrophic impacts from uncontrolled climate change, and hope that communities working across oceans can forge new forms of justice in an era of rising seas.

Quentin Griffiths, co-founder of online fashion retailer ASOS, has died in Pattaya, Thailand, after falling from the 17th floor of a condominium on 9 February, Thai police confirmed.

A seven-month-old Japanese macaque has captured global attention after forming an unusual but heart-warming bond with a stuffed orangutan toy following abandonment by its mother.

Divers have recovered the bodies of seven Chinese tourists and a Russian driver after their minibus broke through the ice of on Lake Baikal in Russia, authorities said.

Ukraine’s National Paralympic Committee has announced it will boycott the opening ceremony of the Milano Cortina 2026 Paralympics in Verona on 6 March, citing the International Paralympic Committee’s decision to allow some Russian and Belarusian athletes to compete under their national flags.

President Donald Trump said on Saturday (21 February) that he will raise temporary tariffs on nearly all U.S. imports from 10% to 15%, the maximum allowed under the law, after the Supreme Court struck down his previous tariff program.

Brazilian President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva has said he will urge U.S. President Donald Trump to avoid a "new Cold War" when the two leaders meet in Washington next month.

Russia launched overnight drone and missile strikes across Ukraine, hitting energy infrastructure in multiple regions, while an explosion in the western city of Lviv killed a police officer and left 24 people injured, authorities said on Sunday (22 February).

U.S. President Donald Trump said he plans to send a hospital ship to Greenland, working with Louisiana Governor Jeff Landry. He announced the move in a social media post shortly before meeting Republican governors in Washington.

Start your day informed with AnewZ Morning Brief. Here are the top news stories for the 22nd of February, covering the latest developments you need to know.

Islamic State claimed two attacks on Syrian army personnel on Saturday (22 February), saying they marked the start of a new phase of operations against the country’s leadership under President Ahmed al-Sharaa.

You can download the AnewZ application from Play Store and the App Store.

What is your opinion on this topic?

Leave the first comment